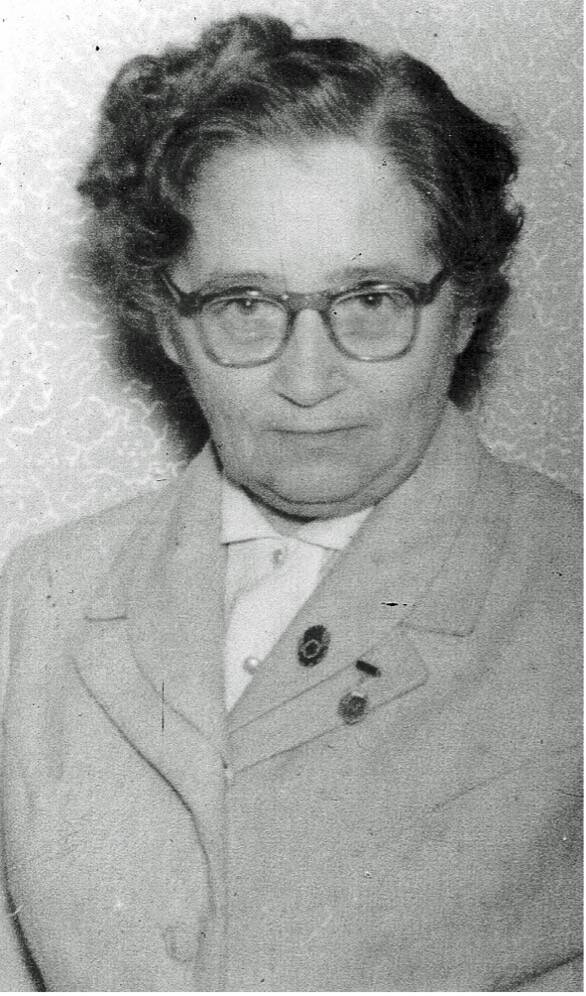

Emilia Salit-Aleksandrovitch

When Annie Salit (Grandma Davidson) came to England in 1895, half the family stayed in Lithuania. From those twenty people - in Vilna and in Kaunas - only one person survived after the holocaust - Emilia Salit - a doctor. One day last year I found her name in an article about Jewish doctors who saved other Jews during the war. Emilia worked in the Vilna ghetto and it was noted in the book that she was credited with preventing the outbreak of infectious diseases in the ghetto. But I found in the bibliography that Emilia herself had written a chapter in a book of memoirs about Kaiserwald - the Nazi camp in Riga. This is her story.

I was the Camp Doctor

I was the Camp Doctor

This memoir was originally published in Hebrew in "Fighting women: The story of a Nazi forced labor camp, AEG." Tel-Aviv: Association of Vilna Jews in Israel, 1979. We are grateful to the Irgun Yotsei Vilna for their help, and also to Adam Noble, Judy Frankel, Rachel Misrati and Yoav Misrati who supported the background research for this translation.

After the liquidation of the Vilna ghetto

After the liquidation of the (Vilna) ghetto, I was transferred in a sealed cattle wagon together with other Jewish women and girls to the Nazi concentration camp Kaiserwald. The Germans ran there a mixed outfit - both slave labour and extermination. Deciding which as they saw fit, but also of course randomly. They didn’t invest time in selecting who-and-who. A lot was dependent upon pure luck, including life and death.

I was somehow lucky and was sent with one of the groups of women to the A.E.G. slave-labour camp in Riga that manufactured specifically for the German army. I was not registered with them as a doctor, and in this apparently I was also lucky, since a doctor or any other Jew with an academic qualification was far from being a ‘persona grata’ for the Germans. On the contrary, they required that people with that status should be the first to be erased from under God’s heaven.

Arriving at the camp

Nevertheless, when I arrived at the camp and when I saw what was going on there, tens and hundreds of women in conditions of malnutrition going out every day to hard work without being given any medical help when they needed it, or in the case of accident at work, so that even a nurse was not available to them, I decided to reveal myself. I had the feeling that I would not be harmed here for being a doctor, and also if they ignored my existence as such and if they didn’t actually cooperate with me, at least they would not bother me much either, since providing minimal medical assistance was an essential need for them as well, as a regime of horror, in order to achieve their goal - productivity of labour and the greatest possible output - a goal that was not always possible to achieve by means of their ‘final solution’.

If my memory today is not mistaken, that was my second reflection. The first thought that arose in my mind was to carry out things, without asking, and without considering anything. By any means. By a decisive decision. With boldness and impudence. I would almost say German impudence. Of all my teachers, in this area, the area of being brazen-headed, it was possible to learn a great deal from them, of course. This first thought of mine did not take into account the danger involved. As a physician and as a Jew, I saw this as a decree of conscience only and ignored all other considerations: To help my poor sisters as best I could, even though my own situation was no different from theirs.

Setting up a clandestine clinic

I found there some sort of room that was not yet occupied, and in it thirty sleeping places. ‘Thirty beds’ I said to myself. It would be possible to hospitalise patients there, of that number. I said that and mentioned it to some of my friends in the camp, and immediately set to work, without announcing it to anyone else, and without getting permission for it.

Very quickly the Germans of course insisted on it. The ‘bird from heaven[1]’, in this case the ‘Blitzmaiden’, as the women of the camp called her, who was in charge of us, on behalf of the Gestapo, ‘of course led the voice’ wherever was necessary. And as I had guessed in the beginning, they shut their eyes and allowed me to continue without talking to me at all, and without saying a word.

Getting medicines, and doctoring records

I began to look for sources of medicines. The only source was, of course, their ‘medical centre’ in Riga. Women from the camp that were sent to the town to work began to look for a foothold there. Polish doctors were working there who came to us sometimes. We also looked for medicines in every other way.

There was a period when they took out medicines from the Chief Physician there himself. Not particularly from a ‘love of Mordechai’ but for some personal reason of his own, according to what I was told. And more. Despite this I suffered constantly from a continuous lack of medicines. Particularly for more serious situations, specifically those that I had to treat as quickly as possible, so that they would not be discovered. In the case of infectious diseases the situation was several times worse: a/ so that they wouldn’t be discovered, and sent for ‘accelerated treatment’; b/ to genuinely prevent an infectious epidemic. For whatever troubles might arise, I edited and managed a card-file of patients on which was recorded, of-course, attenuated and incorrect information. ‘It will be easy to prove through this that no-one is too sick with an infectious or more serious disease, and these are only mild illnesses resulting from fatigue and the like,’ I thought in my heart.

I myself was subjected more than once to the danger of infection and the danger of physical collapse, since I slept in ‘the Rvir’ as the room was known, and was in contact with my patients 24 hours a day. This meant providing help at the necessary time, including nights. I lost a lot of weight, like the other women in the camp, and I was never more than 30-32 kg. (5 stone). But I swore to myself - among other things out of personal pride - that as long as I was here I would do everything to prevent anyone from being sent out of this room to the ‘central hospital’ - in other words to the death camp. So, although we saw ourselves as ‘god-forsaken’, one could say that God was there in my being able to help, and in my success in the mission I set myself, up until the day on which I was taken from the camp.

The 'Blitzmaiden'

However the real danger crept up on me from a different place, from the German ‘Blitzmaiden’ - who ruled the roost at the camp and always tracked and spied on me, arranged opportunities for ‘visiting the sick’ in ‘Rvir’ and informed on me in the ‘right places’ as she saw fit. From her point of view there was no doubt that I broke very many prohibitions, since it was not difficult to diagnose infectious diseases in the patients, or other transgressions on my part, when I took on myself responsibility as the doctor of the camp.

One day a Gestapo soldier with a sub-machine gun appeared in front of me outside, and beckoned me to go to him. I went out, without saying anything. He indicated that I should follow him. In some forgotten corner of the place, where no-one could see, he ordered me to stand in front of him, while keeping his sub-machine gun trained on me, still without uttering a word. For some reason I was not scared at all. I remember that I gave no sign of fear and made no request for mercy. But I also showed no contempt. And so, when I appeared entirely indifferent to his action, I turned my back on him, and I went away from there quietly, also without uttering a word. He didn’t shoot me, and I didn’t react like Lot’s wife in the Bible. I didn’t look back when he turned and went away. I wonder if just because of that, that I was not, like her, turned into a pillar of salt.

The Instinct for Life - and a Birth

When I reflect today on that incident, or others that occurred to me in this camp or another, it is difficult for me to explain to myself the reason for the lack of fear that shrouded me in most of the incidents. A situation that isn’t natural at all. Maybe because I was tired of that life, as were many others in the camp and again it no longer bothered me to be shot or burned – and just be rid of it all. But I think that that was not exactly my feeling then, because I remember also that I was always anxious about the fate of my patients in ‘Rvir’ and I knew that my death would be a great loss to them, and would even cause the death of some of them. Also the instinct for life, that is the desire to stay alive, did not entirely foresake me. On the contrary, I wanted to stay alive in order to finally arrive at the gates of redemption that at the back of my mind I believed in with all my heart, like other women in the camp. I was close to this group of women and we encouraged each other.

My only conclusion, today as then, is: that the chutzpah that I adopted is what protected me. It is simply that chutzpah increases your courage. And maybe I am also a bit courageous and chutspadik by nature. Otherwise, to this day, it is difficult for me to explain these events. Such as the incident of childbirth in Rvir in the dead of night. The story of a woman who was pregnant before she arrived at the camp. She put off dealing with it, and now there was no place to carry out an abortion. That is to say: its fate was sealed. After she came to me, and I saw her ‘disgrace’ I concluded that even if we were both killed, it was my duty to rescue her from her distress - come what may. And so, the women gave birth. She stayed in the camp, and she stayed alive. The baby also survived. I passed it for adoption to a decent Christian family in the town, via one of our women, and via a Latvian woman who worked in the factory, after I received reliable information about the family.

The story of how and why the woman managed to reach the camp up to the birth, a little with my help, etc. is of course a human story, of interest in itself, but here we are dealing with facts and not a literary description, therefore I will leave a full description of how things evolved to the imagination of the reader.

The Broken Leg

And another story of an abortion… oh, the story of a broken leg, and what happened to the woman who broke her leg. I was surprised that there weren’t many cases like that in those conditions, of hard and gruelling labour, accidents, electric-shocks, all in the shadow of fear and helplessness from malnutrition. It was essential to put the leg in the plaster, otherwise I saw that she would lose the leg, and then the owner of the leg herself would be lost, one way or another. I demanded from the Senior Commander (the Hauptscharfuhrer) a vehicle to take her into town for a leg-cast. I demanded in the way a doctor would demand in normal times in his place of work. I demanded - and to my surprise I received permission. And I brought her to the city hospital in Riga, and I appealed to the Polish doctors who were employed there. They complained to me, saying that I was constantly bothering them with the deliveries and requests for medicines, etc. and I was making life difficult for them. However, I blocked my ears and refused to listen. I demanded from them that they should fulfil their duty as doctors, as they had once sworn to do. And thus, the woman was hospitalised there.

The German driver who brought me there agreed to drive me back to the camp, but on the way he reconsidered and ordered me to get down from the vehicle. He claimed he had another more important duty. If I remember correctly, he was talking about a pretty Aryan woman he had to give a lift to. “Blue eyes and blond hair”. Of course, he also wanted to insult me since I had been shaved twice and my bald head was covered with the famous white scarf. Apparently my feminine beauty didn’t attract him, and so I jumped down… I reached the camp on foot.

At SS Headquarters

Just as I thought, finally the evil ‘Blitzmaiden’ managed to defeat me. Her harmful words worked, apparently. One day two armed Gestapo men arrived. They also stood in the doorway and gestured me to accompany them. They put me onto the military vehicle, standing next to me like the angels Michael and Gabriel, to my right and to my left, in case, God forbid, I should escape from them, and brought me straight to the SS headquarters in the city. I don’t remember if I saw any of the women-colleagues on the way, or whether I waved goodbye to any of them…

I arrived at the ‘destination’. My guards got me to climb down, and sent me in, and disappeared. I didn’t set eyes on them again. I think that they didn’t pass on a report about me to anyone. There were other women like me there. There was a work-group there. No-one even glanced over or looked at me. I stood there with all the other women. Eventually someone came up to me with a list in his hand.

‘What do you want?’ he asked me.

‘To work’ I answered him.

He asked my name, and searched down the list.

‘You’re not on the list. I don’t need any more women labourers.’

‘Two more working hands wouldn’t go amiss,’ I answered. “It’s never worth wasting a pair of hands that want to work.’ I spoke as if I was teaching him a lesson in work practice and courtesy. I felt the tone of chutspa in my words.

He didn’t answer me. He continued to look through his list of women. And gave orders. I immediately joined the women and went with them to where they were going. I behaved, as one would say, as if it was quite normal. I went out with them to work. Building work. I slept with them, and I ate from their ‘morsels’. There were also Polish laborers working in the building. They were ‘free’, and of-course of higher status than us Jewish women. But we almost had a shared language with those Polish workers. In the end we learned quite a lot about Polish culture.

Escaping the forced march to the 'Fatherland'

Life was unbearably hard, the work grueling. Sub-human conditions. A life without a future. In the shadow of the fiery furnace. But we continued until the saviour - the Russian army - arrived at the gates.

Then chaos broke out amongst them, but they still didn’t let us go. They dragged us off with them. Even them they separated us, to the left and to the right, as is the custom of the German world. The younger and healthier women were directed to the right, as they could still perhaps be useful to the German ‘fatherland’. I however was sent to the left. But luckily just then a group of Hungarian women arrived. Young Jewish women. I seized the moment, and immediately I was one of them. I mingled in amongst them.

We began to march, almost barefoot. In deep snow. Somehow I had a large pair of old army boots, or building worker’s boots, or something like that, that I had once managed to ‘acquire’. And one blanket - the only possession that each of us women in the camp had. I could sail around in those boots - all 30 kilo of me, but they were better than nothing.

The route was via Torun (in Poland, another A.E.G. camp) to Germany, their Promised Land. ‘Deutschland uber Alles’. And not every person gets to live there, whereas we would indeed be given this great privilege!

I drifted to the side. I sneaked away from the convoy and hid between the piles of snow along the edges of the road. The blanket was my succour.

Freedom

After this, when the camp convoy disappeared, I began to walk on my own in the direction of Bromberg (30 miles from Torun). Exactly how long I walked I no longer remember. I only remember that suddenly I met a woman dressed in elegant winter clothing. She spoke Polish and was heading into town. I walked along with her. When we reached the main road of the town she sneaked away from me and disappeared. I was left alone.

I knocked on the door of a Polish house. The street was swarming with Germans. They closed me in a crate a meter high, to stay for one night. It was the house of a Polish tailor who worked for the Germans. His daughter was a nurse, but unemployed for some reason. In the morning they let me out to me ‘freedom’ - once I had promised in the name of everything that was holy that I would not reveal to a soul where I had spent the night.

I didn’t lose my wits. I called upon my ‘angel of chutzpah’ to help, and I made my way to the Polish hospital in the town. The daughter (the nurse) was willing to accompany me and show me the way. We went a long way in the winter weather.

In the hospital I asked for the Director. The “Chief Polish Physician”. The Polish he spoke didn’t sound to me like that of a native Pole, and he gave me the impression of being a German posing as a Polish man, and wishing to remain as such. I immediately saw that this was a way of putting pressure on him, and my confidence grew.

I presented him with a certificate of being a Chief Physician that I had kept with me. Just then one or two posts were vacant. An elderly nun who had worked there for years had decided to retire. And the Chief Nurse, a German woman, had abandoned the hospital and disappeared. In her footsteps apparently other German doctors also left.

The Director explained to me that there was a place for a Chief Physician in Children's Department. I agreed it once to take up the post, despite the fact that I had hardly ever worked with children. I was allocated the room of the Chief Nurse who had run away, a room that was surprisingly well organised. And it was pleasantly warm.

I threw off my big boots, and put on the pleasant indoor shoes that I found there, apparently belonging to the Chief Nurse. I stretched out on the comfortable bed for a brief rest. Ah. How good and how pleasant it is to be a human being to every friend! Never again would the Germans who were even now running away like rats from their sinking ship, never would they be able to oust me from here. And if I do go, I will go under my own steam, of my own free will. Long live freedom!.

Create Your Own Website With Webador